In 1976 I got a call at Alembic from John McVie of Fleetwood Mac. The band was ensconced at the Record Plant in Sausalito to record their second album, to be known as “Rumours,” with Lindsey Buckingham and Stevie Nicks, and John invited me down to meet them all, check out the setup on his early Alembic bass, and also see to anything that Lindsey’s Les Paul and Strat might need. Visit I did, and I quickly became very at home with the band and their studio crew of Ken Caillat, Richard Dashut, and Rick Sanchez, as well as guitar tech Ray Lindsey. I visited frequently, partaking in the crazy hospitality, and found that I had a lot in common with Lindsey when it came to musical influences. It might have helped that we were all in a similar state of personal disarray; I, too, was going through a major marital breakup with my wife, Gail, at that point. At least I wasn’t trying to make an album with her at the time!

On one of the funnier nights there in Sausalito, we were all sitting in the control room when in came an excited Richard Dashut with the latest copy of Billboard. “Number one! We’re number one!!” “What?” was the general response. The band’s previous album, “Fleetwood Mac,” their first with Stevie and Lindsey, had been released a year before this, and the band had pretty much forgotten about it, with all the drama and creativity flowing at the Record Plant. Also, at that time, if an album didn’t really take off in six weeks or so, it was destined for failure. The band had written it off, but suddenly they had the hottest selling album on the charts.

This happened the same month Mick and John’s lawsuit against their former manager was settled in their favor. A couple of years before this, at a point when there was barely a band, it being down to Mick, John, and Christine, their manager had hired a bogus bunch of musicians and put them out on the road as “Fleetwood Mac.” Mick and John sued, but in a countersuit, all of their recording royalties from Warner Brothers wound up in an escrow account. The band had to scramble and try to survive on live gigs with a succession of guitar players. When Lindsey and Stevie joined the band, they were doing a lot of covers of earlier iterations of Fleetwood Mac’s material. The new songs that Lindsey and Stevie brought to the “Fleetwood Mac” album changed the direction of the band, but the real impact didn’t hit until they were in Sausalito recording Rumours. Suddenly they were the number one band in the world, and a couple of years worth of royalties broke loose.

John started buying Alembic basses that I’d bring to the studio, and they included the very first carbon fiber necked instrument, a short scale bass in the shape now made famous by Stanley Clarke, and a long scale fretless with a stainless steel fingerboard which can be heard on “The Chain” from Rumours. It’s the one used in the bass intro to the song outro—bum, ba ba bum ba ba ba ba ba booooommmmm before Lindsey’s screaming Strat comes in.

For Lindsey, my main contribution during Rumours was installing an Alembic “Stratoblaster” in his Strat exactly like the one I’d put in Lowell George’s guitar, the one you hear on Little Feat’s live album, “Waiting for Columbus.” For Lindsey, the sound of the electric on Rumours is his guitar with the ‘Blaster gain all the way up, basically destroying a succession of HiWatt amps. Evidently, the HiWatts did not have adequate current protection; they were fine with normal electric guitar output levels, but when we boosted that by nearly 12 dB, the amplifier just tried to pull more and more current through the power transformer, and after about 20 or 30 minutes of high gain sustaining guitar solo, the transformers would literally go up in smoke. Luckily, they had three of them, and every day one would go off to Prune Music to be repaired.

I had started to confront the flaws in the Alembic guitars after meeting Lindsey; we talked guitars a lot, and I built him an Alembic—a beauty—all white with black chrome hardware. But I had known for some time that there was something fundamental in the design that made the Alembic design great for bass but not friendly for guitar players; this was painfully evidenced by our 20-to-1 ratio of bass to guitar production. Most people I discussed this with thought it was inherent in the low impedance pickup and active electronics design; they thought the sound was just too clean for the average rock’n’roll guitar player. While I thought that this theory might have some merit, I still saw the problem as being deeper than that. After all, with the Alembic variable tone control filter it was possible to kind of superimpose the frequency response of a Strat, Tele, or Gibson humbucker over the wide band response of the Alembic pickup, yet that still didn’t sound right. I came to believe that the strings just weren’t moving the right way, being coupled as they were to a heavy bridge set on a sustain block and then to the stiff and high-frequency resonant neck laminate that went through the body from the peghead to the butt. The very construction feature that made Alembics stand out visually and aurally in a positive way was working against us when it came to making a warm and seductive guitar. Further discussions with Lindsey who had purchased an Alembic guitar confirmed my feelings, and I set out to design a completely new instrument.

The trick in a game like this—designing from scratch—is to climb down off the particular design tree you’ve been exploring and go find a new tree. You have to really get back down to the very ground and try to a) forget everything you’ve been doing, and b) don’t forget anything because it might be useful. It requires that you logically justify each and every little decision, and that you do nothing just because “that’s how it’s done” or because “that’s what I know how to do.” It means that you have to start with the results you hope to achieve and work backward, always keeping an open mind, but also trying to work with what you know and what you’ve learned from other people, other instruments, and of things completely outside the musical instrument world.

For me it meant wanting to make a guitar that would combine the warmth I liked in Les Pauls and SGs with the clarity that comes from a Strat, and then I wanted to put a kind of acoustic overlay on that sound as well as the look. I wanted to make an electric guitar that would appeal to an acoustic guitarist used to fine old Martins, Larsons, and Gibsons, and yet would be capable of the kind of full bore electric tones that players like Peter Green, Eric Clapton, and of course, Lindsey Buckingham could get. I guess if you could express the sound I wanted it would be like lemon butter—rich with a tangy touch. And this sound had to be inherent in the instrument itself; it could not be achieved with any old plank of wood by putting just the right pickup on it. It’s all in how the guitar affects the string vibration—that back and forth feedback loop between wire and wood.

I started with the most obvious place, the body. I needed to get away from that neck-through body thing; it did not allow enough contribution from the body wood to warm up the sound. My favorite sounding electrics were the old Les Paul custom—the original version with the all-mahogany body and no maple cap—and the Gibson SG, though I thought it punked out below about “B” on the “A” string and above about “B” on the high “E” string. The common theme between the two instruments is the mahogany body, a well loved instrument wood that can impart a dry tone to acoustic guitars, but a warmer tone with the thicker pieces used in electrics. I also wanted to bring the average weight of the new guitar in at between that of a Les Paul and a Strat—no use sending the players to the chiropractor after every gig. In thinking over what I’d learned about PA speaker cabinet building, echo chamber design and such, I realized that parallel surfaces lead to standing waves, even in solid structures, and that made me wonder if the problem with the SG’s narrower response might be that the parallel surfaces might lead to some kinds of issues with limiting the frequency response, or having resonances too pronounced. These considerations brought me to the idea of arching the surfaces of the top and back, and doing it based on one of the main design features of my favorite vintage acoustic guitars, the cylinder topped Howe-Ormes from the 1890s.

I drew up a set of blueprints for a new guitar that would have a “set” glued-in neck and a mahogany body. For the warmth I liked in the Les Paul customs and SGs, the body was to be mahogany, and I realized I could make a “clam shell” of two body halves with each being 1-¼” thick in the center; that just happened to be the thickness of an Alembic bass body center section on which we glued a ¼” thick top and back. Thus it would use a common lumber dimension with what we were already using. For the neck, I realized that every Alembic bass neck yielded a piece of laminated scrap approximately 20” long, 2-¼” wide, and that could be thicknessed to ¾”. By stacking a heel block on and then scarfing on a peghead, this was perfect for a 15 frets-to-the-body neck that would have the stiffness characteristics—and somewhat the tonal properties of a Strat neck. It would be stiff and not absorb much string vibration, and with a rosewood fingerboard, it would balance the mahogany body nicely. I showed the drawings to Lindsey, discussed the idea of a single pickup with semi-parametric EQ, made a few minor changes, and did a final blueprint. When I took the ‘print down to the studio, Lindsey said, “I’ll take one as soon as you have it done.”

Not long after this, but before I got a chance to build a prototype Model 1, things at Alembic went South…way South. There were a lot of irregularities on the business side of things; there was a lot of money apparently missing; and I instituted an audit and discovered that things were not as they should have been. I wanted an official audit to be done by an independent accountant; I was overruled and subsequently fired for rocking the boat. I learned the age-old lesson that 43% ownership is not 51%, and if the 14% owner had personal reasons for not wanting the boat rocked, well, tough shit for me.

Luckily, I’d moved several years worth of canceled checks to my house where a couple of people and I were digging into how checks had been “coded” and accounted for in the company books. It was not a pretty picture, and I got an attorney involved and moved the accounting to his office. A week later an arsonist burned down my house in Santa Rosa on Pearl Harbor day of 1978. Eventually I settled with Alembic for a financial payout plus taking the design of the Model 1 and my share of the carbon fiber neck patent with me. I learned at that point that you can have justice or get paid, but not necessarily get both at the same time.

As all this was going on, I decided to start up a new guitar company, and so, with the settlement money and the insurance from the house, I started up Turner Guitars with my then-brother-in-law as a junior partner. We set up a shop in Ignacio, in Marin County, and tooled up to build Model 1 guitars. My pal Larry Robinson managed to buy about 300 of the neck scrap laminates from Alembic without them knowing that the parts were going to me; I had my old friend and former employee Jim Furman design the preamp/EQ electronics; and Bill and Pat Bartolini agreed to make the humbucker I’d designed, as I was no longer set up to wind my own pickups.

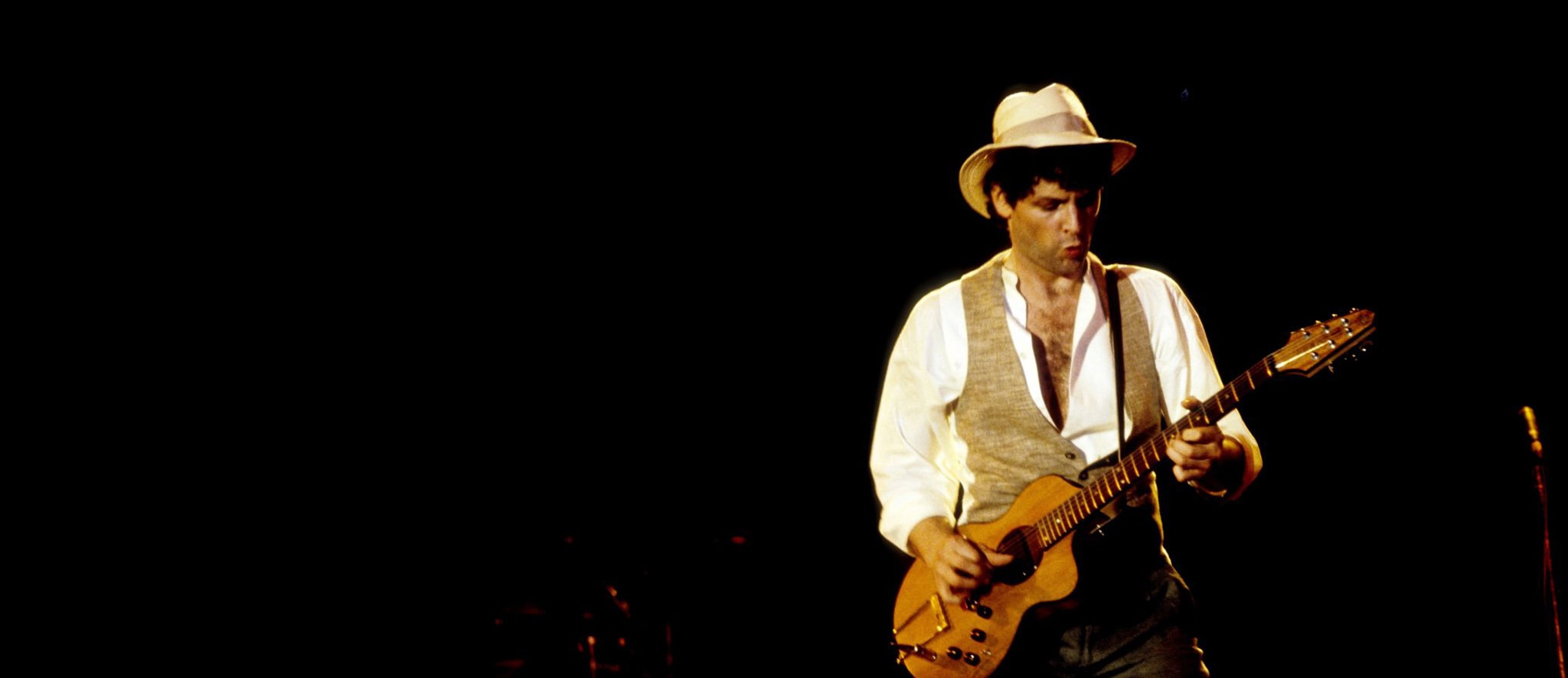

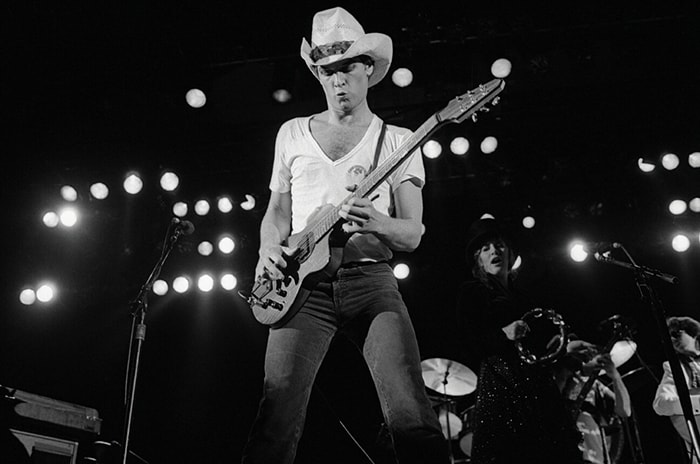

By the end of summer of 1979 I was finishing up the first three prototypes of the Model 1 guitar, and I knew that Fleetwood Mac was going to start the Tusk tour near the end of October. I called Ray Lindsey, Lindsey Buckingham’s guitar tech, and let him know that I had a guitar for him to try out. Ray invited me to come down to Hollywood to the sound stage where the band was rehearsing. I got there on the early side, before the band got in; Ray checked out the guitar and loved it, and he left it plugged in and put it up on a stand plugged in front of Lindsey’s amps, and we walked to the back of the place (it had once been the site of Esther Williams gigantic swimming pool!) and just sat and chatted. Lindsey came in first, went up on stage, picked up the guitar and played it for about a half an hour before the rest of the band came in. I thought it sounded fantastic—exactly the sound I’d had in my head when I first started designing the guitar. Lindsey then shouted back to Ray, “Leave the Les Paul, the Strat, and the Ovation at home. This is all I need now!” Well, fucking make my day! Then the rest of the band came in and started to rehearse. The guitar just sat perfectly in the mix on any and all tunes. Lindsey could play it clean like an acoustic, get a bit more edge, kind of like he was playing a Strat with a clean tone, or crank it up full bore with Santana-like sustain. It did the trick. After about an hour, Mick came back and said, “OK, Rick, you did it. How fast can we get a backup for that guitar?”

By the end of summer of 1979 I was finishing up the first three prototypes of the Model 1 guitar, and I knew that Fleetwood Mac was going to start the Tusk tour near the end of October. I called Ray Lindsey, Lindsey Buckingham’s guitar tech, and let him know that I had a guitar for him to try out. Ray invited me to come down to Hollywood to the sound stage where the band was rehearsing. I got there on the early side, before the band got in; Ray checked out the guitar and loved it, and he left it plugged in and put it up on a stand plugged in front of Lindsey’s amps, and we walked to the back of the place (it had once been the site of Esther Williams gigantic swimming pool!) and just sat and chatted. Lindsey came in first, went up on stage, picked up the guitar and played it for about a half an hour before the rest of the band came in. I thought it sounded fantastic—exactly the sound I’d had in my head when I first started designing the guitar. Lindsey then shouted back to Ray, “Leave the Les Paul, the Strat, and the Ovation at home. This is all I need now!” Well, fucking make my day! Then the rest of the band came in and started to rehearse. The guitar just sat perfectly in the mix on any and all tunes. Lindsey could play it clean like an acoustic, get a bit more edge, kind of like he was playing a Strat with a clean tone, or crank it up full bore with Santana-like sustain. It did the trick. After about an hour, Mick came back and said, “OK, Rick, you did it. How fast can we get a backup for that guitar?”